Exploring Queerness Behind Early Horror Cinema

It should come as no surprise that the queer community and horror films share a strong kinship. From a very early point in cinema, the horror genre has created a platform in which real-life queer issues can be explored in a far more digestible or campy light. It is the strangeness, the brutality, and most of all, the queer themes that have seemingly captivated LGBTQ+ audiences for decades.

It should come as no surprise that the queer community and horror films share a strong kinship. From a very early point in cinema, the horror genre has created a platform in which real-life queer issues can be explored in a far more digestible or campy light. It is the strangeness, the brutality, and most of all, the queer themes that have seemingly captivated LGBTQ+ audiences for decades.

While queerness in major horror films is typically deciphered through heavy undertones, the genre has created a freeing canvas for LGBTQ+ individuals to traverse their struggles, both through creation and interpretation.

When exploring the intersectionality between the LGBTQ+ community and horror cinema, it is crucial to consider how this connection was solidified historically, largely through the legacy of early filmmakers. To discuss early queer horror films is to discuss acclaimed, F.W. Murnau and James Whale, two of the genre’s most influential names. It is these queer creators who have shared with the world such iconic films in horror including Nosferatu (1922), Frankenstein (1931), and The Invisible Man (1933), to name a few. Without directors like F.W. Murnau and James Whale, the relationship between queerness and horror might not have grown so close, creating an ironically safe space for queer audiences.

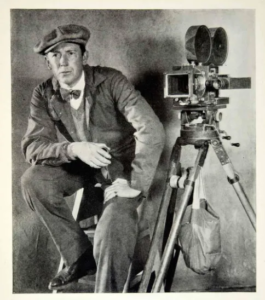

F.W. Murnau

It is imperative to begin the story of director F.W. Murnau by prefacing it with the notion that although some historians refute the claim, it is widely accepted that F.W. Murnau was a gay man. Born in Beifeld, Germany in 1888, and during a time in which homosexuality in the country was illegal, it is no shock that historians share no concrete footing whether the late director was an openly gay man, or if this concept came to fruition through the ever-present gossip surrounding Murnau. Nevertheless, the late Murnau’s letters, diaries, and films all subtly reflect the director’s queerness.

It is imperative to begin the story of director F.W. Murnau by prefacing it with the notion that although some historians refute the claim, it is widely accepted that F.W. Murnau was a gay man. Born in Beifeld, Germany in 1888, and during a time in which homosexuality in the country was illegal, it is no shock that historians share no concrete footing whether the late director was an openly gay man, or if this concept came to fruition through the ever-present gossip surrounding Murnau. Nevertheless, the late Murnau’s letters, diaries, and films all subtly reflect the director’s queerness.

Despite the increasing fascism that forced Murnau to not only possibly hide his sexuality but also move to the United States where he later pursued an eccentric career in Hollywood, it was in Germany that Murnau received his first big breakthrough.

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, or Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens, was released in 1922, and was an unlicensed adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which had only been around twenty-five years old at the time of its release. The film was a marvel in its own right; actor Max Schrek consumed the role of the titular vampire, Count Orlock, searing the icon into the minds of frightened audience members.

Despite the impressiveness of the film, Nosferatu is a title with quite a tumultuous history. Because the picture was an unauthorized adaptation of the previously mentioned novel, the film was taken to court for copyright infringement by Florence Stoker, the wife of, at the time, deceased Bram Stoker. The team behind the Nosferatu was ordered to destroy all copies of the picture and in doing so, became bankrupt. Through sheer luck some copies survived, allowing F.W. Murnau the eventful push his career needed.

After the storm that was Nosferatu, Murnau experienced a career of heavy ups and downs shrouded in rumors and gossip. It was only after his automobile-related death in 1931 that the information about Murnau’s homosexuality came to light. According to tabloids at the time, Murnau had hired a 14-year-old valet driver who was in the car with him at the time of the accident.

Numerous rumors surrounding the two individuals sprouted from the untimely death of the late director. These rumors were so pervasive that only eleven individuals attended the director’s funeral, among them the renowned Gretta Garbo.

Despite the rumors and the sheer dizziness that comes with learning of F.W. Murnau’s history, it is an undeniable fact that the director has ingrained himself into queer horror history. Murnau is a conclusive pioneer of the horror genre and should be celebrated for such.

James Whale

Although F.W. Murnau may not be a household name for everyone, the renowned director, James Whale, has found a way to the hearts of many.

Although F.W. Murnau may not be a household name for everyone, the renowned director, James Whale, has found a way to the hearts of many.

Born to a large working-class family in Dudley, England, Whale began life humbly, attending various schools before dropping out to begin his early career in cobbling. Through this, Whale had an innate love and talent for the arts and when enlisted in the army during World War I, Whale staged plays for the camps in which he had been taken prisoner. It was after the war that Whale pursued a full-time stage career.

During this time, Whale was openly homosexual, despite the act being illegal in England until the far-off future of 1967. This fact, of course, did not stop the ambitious artist, who in 1929, was pulled to Hollywood through the success of his film, Journey’s End. This accomplishment secured him a contract with the esteemed Paramount Pictures and introduced him to producer, David Lewis, who would later become Whale’s partner of 23 years.

Following his stint with Paramount Pictures James Whale truly took off in the horror genre. Partnering with Universal Studios, he directed his first horror feature: Frankenstein (1931). To say the picture was a success is an understatement; critics at the time claimed it was one of the best films of the year.

Whale, despite never naming himself as a horror director, was synonymous with the genre as Universal pushed him to create another terrifying feature. Even so, it wasn’t until two years later that the director pumped out another phenomenal picture, The Invisible Man.

Whale, despite never naming himself as a horror director, was synonymous with the genre as Universal pushed him to create another terrifying feature. Even so, it wasn’t until two years later that the director pumped out another phenomenal picture, The Invisible Man.

To his dismay, it was around this time that James Whale found himself pigeonholed into a purely horrific creator. Still, ever the unique individual, Whale’s subsequent films were romance and drama-oriented, a change that did not sit well with audiences and critics. His films outside of the genre never reached the acclaim of the previously mentioned pictures, forcing Whale to leap back into horror and back into the story of Frankenstein.

The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) was a raving success and is a film that is timelessly interpreted as a queer narrative. The dejection and isolation that Frankenstein’s monster experiences in searching for humanity resonates closely with queer viewers. Additionally, Doctor Pretorious, a flamboyant and unmarried older man (usually interpreted as a gay man), stands out as one of the only characters, albeit the antagonist, who views the creature as a respectable figure.

It was around 1941 when James Whale retired from his film career but was subsequently persuaded back into the arts by his partner, David Lewis. As a result, Whale met Pierre Foegel, a twenty-five-year-old bartender in France. So infatuated by the young man, Whale sought to bring him back to the States, causing such a significant rift to form between Lewis and himself that the two separated, but continued to stay friendly.

It was around 1941 when James Whale retired from his film career but was subsequently persuaded back into the arts by his partner, David Lewis. As a result, Whale met Pierre Foegel, a twenty-five-year-old bartender in France. So infatuated by the young man, Whale sought to bring him back to the States, causing such a significant rift to form between Lewis and himself that the two separated, but continued to stay friendly.

Whale soon after met a tragic end; at the time, the sixty-seven-year-old director committed suicide, leaving David Lewis a note that did not surface until many years after Whale’s death.

James Whale was an extraordinary individual with a profound talent for the arts. Without such classic monster features, the state of horror cinema and its relationship with the queer community would likely not have gotten as far as it did.

It is clear why such directors have left a lasting impact on, not only the queer community but on the entirety of cinema. Both F.W. Murnau’s and James Whale’s contributions to the genre have become timeless and have helped in starting a formidable bisect of horror lovers as a whole. Their visions have uniquely shaped not only the landscape of genre films but established a powerful bond between LGBTQ+ horror enthusiasts, demonstrating how early cinema can both reflect and influence queer dialogues and identities.

Written by Nel Delossnatos Barandica

Social Media Links:

Email: Neliabarandica@gmail.com

Discord: @nyx5204